RECONSTRUCTION OF DANISOVAN PAIR ANIMATION IN 3DS MAX

|

| 3D RECONSTRUCTION OF DANISOVAN PAIR |

Denisovans : were an extinct group of archaic humans who lived across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic periods. They are primarily known from DNA evidence and a few fossil remains, including a molar and a finger bone discovered in Denisova Cave in Siberia. In 2008, a team of archaeologists exploring Denisova Cave in Siberia unearthed a fragment of a finger bone. This tiny piece of fossil initially seemed insignificant, but DNA analysis revealed it belonged to a previously unknown human species. Later, molars and a jawbone from other locations confirmed Denisovans’ existence.

Key Facts

About Denisovans:

Time Period:

They lived from around 285,000 to 25,000 years ago.

Physical

Traits: Denisovans likely had dark skin, eyes, and hair, with a

Neanderthal-like build but larger molars.

Genetic

Legacy: They interbred with both Neanderthals and early modern humans. Some

modern populations, particularly Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians, and

Filipino Negritos, carry Denisovan DNA.

Discovery:

The first Denisovan individual was identified in 2010 through mitochondrial DNA

extracted from a juvenile female’s finger bone.

Hybrid

Evidence: A first-generation hybrid, nicknamed "Denny," was found to

have a Denisovan father and a Neanderthal mother.

Possible

Species Name: Some researchers propose naming them Homo denisova or Homo

altaiensis, though no formal classification has been established.

Denisovans

remain a fascinating mystery in human evolution, with ongoing discoveries

shedding light on their interactions with other hominin groups. If you're

interested in their artistic depiction, I’d love to brainstorm ideas with you!

Denisovans played a crucial role in shaping modern human genetics and adaptability. Though mysterious due to the scarcity of fossil evidence, their genetic legacy has had profound impacts on various human populations.

Key

Contributions to Human Evolution:

Genetic Adaptation: Denisovan genes contributed to physiological traits that helped modern humans survive in extreme environments. For example, Tibetans inherited a variant of the EPAS1 gene from Denisovans, allowing them to thrive at high altitudes with lower oxygen levels.

Interbreeding

with Homo sapiens: Denisovans interbred with early modern humans, influencing

the genetic diversity of present-day populations. Their DNA is found in

Melanesians, Aboriginal Australians, and some East and South Asian groups.

Possible

Cultural Influence: Though speculative, Denisovans may have exchanged

knowledge, tools, and survival strategies with early Homo sapiens, much like

Neanderthals did.

Denisovans

highlight the complexity of human ancestry, showing that modern humans didn't

evolve in isolation but through interactions with other archaic hominins. Since

you're deeply invested in reconstructing prehistoric life, I'd love to

collaborate on visual depictions of Denisovans—perhaps integrating artistic

storytelling into their evolutionary significance! What aspects intrigue you

the most?

Ancient

DNA puts a face on the mysterious Denisovans, extinct cousins of Neanderthals:

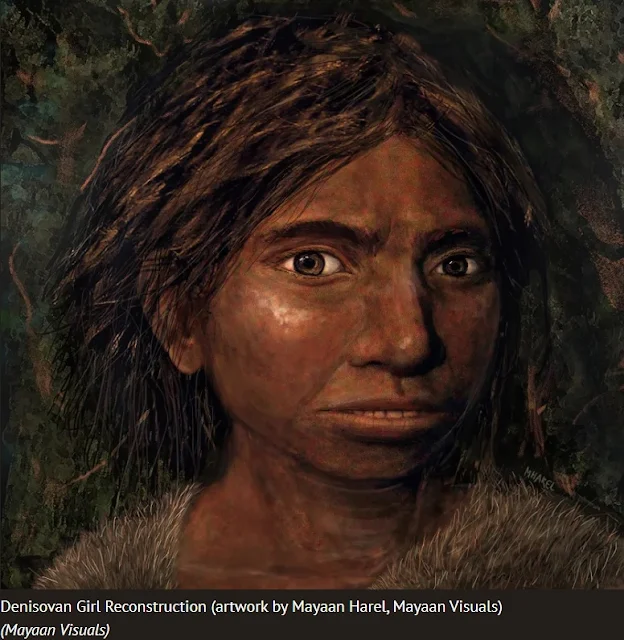

Many of us can picture the face of a Neanderthal, with its low forehead, beetled brows, and big nose. But until now, even scientists could only guess at the features of the extinct Denisovans, who once thrived across Asia. For more than 10 years, these close cousins of Neanderthals have been identified only by their DNA in a handful of scrappy fossils.

Now, a new method has given the Denisovans a face. A recently developed way to glean clues about anatomy from ancient genomes enabled researchers to piece together a rough composite of a young girl who lived at Denisova Cave in Siberia in Russia 75,000 years ago. The results suggest a broad-faced species that would have looked distinct from both humans and Neanderthals.

Ludovic

Orlando, a molecular archaeologist at the University of Copenhagen who wasn't

involved in the work, calls the approach "clever." But he and others

caution against making specieswide generalizations based on a single

individual.

Perhaps 600,000 years ago, the lineage that led to modern humans split from the one that led to Neanderthals and Denisovans. Then about 400,000 years ago, Denisovans and Neanderthals themselves split into separate branches. Denisovans ranged from Siberia to Southeast Asia and may have persisted until as recently as 30,000 years ago, based on their genetic legacy in living Southeast Asians.

Hundreds of Neanderthal skeletons, including intact skulls, have been found over the years. But the only fossils conclusively linked to Denisovans are a pinkie bone from the girl plus three teeth, all from Denisova Cave, and a recently identified lower jaw from China's Baishiya Karst Cave.

Then in

2014, researchers introduced a novel method based on epigenetics—a set of

molecular knobs that can turn gene expression up or down—to analyze gene

regulation in long-extinct hominins. One such knob is a chemical modification

called methylation, which silences gene expression. In methylated DNA, one

nucleotide, cytosine, degrades over thousands of years into a different end

product than usual. By tracking that degradation in an ancient genome,

scientists can create a methylation "map."

Liran Carmel and David Gokhman, geneticists at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and their colleagues applied this method to DNA in the girl's pinkie from Denisova Cave. They compared the girl's methylation map with similar maps of modern humans, Neanderthals, and chimpanzees, focusing on areas where the degree of methylation differed by more than 50%.

To find out

how Denisovans' unique methylation patterns might have influenced their

physical features, the researchers consulted the Human Phenotype Ontology

database of genes known to cause specific anatomical changes in modern humans

when they are missing or defective. Because methylated genes are "turned

off," they may have effects comparable to those of the genes in the

database, making it possible for researchers to infer Denisovan anatomy.

The method can't provide exact body measurements. "We can say [Denisovans had] longer fingers [than modern humans for example], but we cannot say 2 millimeters longer," Carmel explains. In total, the researchers discovered 56 Denisovan anatomical features that may have differed from humans or Neanderthals, 34 of them in the skull. As expected, the Denisovan girl looked fairly similar to a Neanderthal, with a similarly flat cranium, protruding lower jaw, and sloping forehead, the researchers report this week in Cell.

Yet she also had key differences. The reconstructed face was notably wider than that of a modern human or Neanderthal, and the arch of teeth along the jawbone was longer.

A test of the model came while Cell's editors reviewed the paper. Another team concluded based on ancient proteins in the Baishiya jawbone that it belonged to a Denisovan. Carmel and colleagues eagerly matched their model Denisovan to the real thing, and found a close fit: The jawbone was wider than that of either humans or Neanderthals, and there were hints that it protruded about as much as in Neanderthals but more than in modern humans. "It almost perfectly matched our predictions, which was very nice for us," Carmel says. The team's predictions also match skull fragments from Xuchang, China, that some argue belong to a Denisovan, he adds, and the method may help identify additional Denisovan specimens.

Because the current study is based on a single individual and the technique only returns relative measurements, researchers caution that it's an imperfect reflection of what the species looked like. Only more Denisovan fossils can confirm whether this portrait is accurate, says Gabriel Renaud, a bioinformatician at the University of Copenhagen, who adds that he wishes the authors had publicly released their computational methods so that others could replicate the findings.

"If you

were to find a single Homo sapiens fossil and it's an NBA basketball player,

then you might conclude that Homo sapiens were 7 feet tall," he says.

"It's an interesting approach, but we can't verify the predictions until

several Denisovan skeletons are found."

Denisovans

– 18 foot Human Giants who lived 40,000 years back in Asia:

Human

history, specially the part where man got the intelligence and ability to

develop himself and the surroundings, has been held hostage to the limits of

Western religious ideology. For years,

historians have been loathe to accept that real development and sophisticated

work by man started before the advent of Abrahamic history. That Abraham’s folk-lore and mythology is not

the starting point of man’s consciousness.

Denisovans and their work is yet another challenge to the accepted

mythology that passes off as history in most text books.

How big were

Denisovans

In 2008, an excavation in the Altai region of Siberia unearthed a bone of a small girl and a tooth from an adult individual. As per the DNA testing, the girl had roamed the Earth approximately 41,000 years ago. Interestingly, the tooth was over 2.5 times the human tooth. And, these body parts were from a new species unknown hitherto to historian. A species that lived between 700,000 to 40,000 years ago. The species has been classified as Homo sapiens ssp. Denisova and Homo sp. Altai (where ssp is sub-sub-species and sp is sub-species).

Now what is

most interesting is that this species of Homo Sapien was of an unusual size –

as much as 3 times a modern 6 ft tall man!

It is not easy to fit that big a tooth in a human jaw bone and the size

based on the right jaw would take the adult to that size. There is another

interesting fact about the body and size of a Denisovan. He had a very large brain – compared to

humans and Neanderthals. The humans have

a brain volume of 1450 cc (cubic centimeters), Neanderthals had 1600 cc while

the Denisovans had 1800 cc. There might be a tendency to think that mating

between modern humans and archaic humans such as Neanderthals and Denisovans is

a very strange behavior and therefore there must be something unusual or

different about populations that engaged in such behavior,” Stoneking added.

“Instead, I think the picture we are getting from both this work as well as

from analyses of genetic data from all modern human populations is that there

are two things humans like to do — migrate and mate — and the product of these

two is going to be admixture.”

It therefore seems that Denisovans were mating with the modern humans as late as 40,000 years back. Of course, the Denisovans shared the most – 4-6% – DNA with the Melanesians, which are the people from Papua New Guinea and Bougainville Islanders.

Their

analysis shows that, in addition to Melanesians, Denisovans contributed DNA to

Australian aborigines, a Philippine “Negrito” group called Mamanwa, and several

other populations in eastern Southeast Asia and Oceania. However, groups in the

west or northwest, including other Negrito groups such as the Onge in the

Andaman Islands and the Jehai in Malaysia, as well as mainland East Asians, did

not interbreed with Denisovans.

Were

Denisovans so ‘uncivilized’?

The archeologists have found a bracelet from the Denisovan caves that date back to 40,000 made of Chlorite, which is a stone that reflects sun rays.

‘The

bracelet is stunning – in bright sunlight it reflects the sun rays, at night by

the fire it casts a deep shade of green,’ said Anatoly Derevyanko, Director of

the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography in Novosibirsk, part of the

Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

The bracelet is made of Chlorite stone that is formed under pressure at high temperature at certain depths in earth. It is not “lying around” here and there and has to mined! It is anyone’s guess as to what a 18 foot large Homo Sapien was doing with jewelry made of a translucent stone that needs to be mined. Right? Well Check out the bracelet pics and then we will discuss something even more shocking! (All the pictures below from Siberian Times)

Hovers explained that until 55,000 years ago (when the Denisovans went extinct), the 270-square meter cave was inhabited on and off for some 250,000 years by several forms of humans, including Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and Denisovans — as well as hyenas and bears who clearly relished their bones. After several of the cave’s human bone fragments underwent DNA analysis in Germany, it was discovered that one microscopic piece of bone was of a human who was neither Neanderthal nor Homo sapiens, but rather a new kind of human.

“It was the first time in the history of research that a taxon” — a taxonomic group — “was identified by DNA analysis,” said Hovers.

After that first tiny fragment of a pinkie finger, scant other clearly determined Denisovan bone fragments were discovered, including a few teeth and recently a jawbone in Tibet.

“There are very few remains, but we are very lucky because we live in the middle of a major revolution in genetics — the ancient DNA revolution,” said Carmel.

After isolation of the Denisovan DNA, it was found that traces are still found in some modern humans, including some six percent of aboriginal Australians, Malaysians and some other Southeast Asian populations. Likewise, Carmel said that Denisovan DNA may aid Inuits to adapt to extreme cold, and Tibetans to live in high altitudes. However, DNA analysis alone does not allow scientists to reconstruct physical characteristics, said Carmel, quipping that were DNA analysis alone able paint a person’s picture, police forensics units all over the world would have a much easier time apprehending suspects. Purely based on Denisovan DNA, scientists merely know that the people likely had moderate to dark hair, eyes, and skin, he said. Essentially, the activation or deactivation of single genes can affect observable physical, phenotypic characteristics. To arrive at how a skeleton is influenced by the on-off methylation switch of certain genes, the team of scientists cross-checked physical characteristics with a database of single-gene diseases, said Carmel. Some monogenic disorders can point to changes in bone structure such as a small pelvis, he explained.

“We did this trick for all genes relevant to skeletal morphology and came up with a detailed anatomical prediction for how Denisovans look like,” said Carmel.

“We got a

prediction as to what skeletal parts are affected by differential regulation of

each gene and in what direction that skeletal part would change — for example,

a longer or shorter femur bone,” said Gokhman in a Hebrew University press

release..

Over a

three-year study, the team tested its methylation-based theory by drawing up

physical characteristics of Neanderthals, Homo sapiens and chimpanzees based on

their DNA’s methylation patterns. Based on the charted on-off switch of certain

physical genetic characteristics, Carmel said the team’s predictions had an 85

percent accuracy.

The team then applied the methylation methodology to the Denisovans and found 56 anatomical traits which were different from modern humans and Neanderthals, 34 of which were in the skull, and probably included a longer dental arch and no chin.

The most striking characteristic, the Denisovans’ very wide skulls, made Carmel reexamine a mysterious recent find in China.

In 2017, the archaeological world took notice when unusual 100,000-year old skulls were discovered in Xuchang, China. Carmel said that based on the methylation of the DNA, the projected Denisovan skulls would be a match for seven out of eight unique traits on those Chinese skulls.

“Our work suggests the Chinese skulls are Denisovans,” said Carmel

“Denisovans and Neanderthals are our closest evolutionary relatives — they are humans,” said Carmel. “For people who study human evolution, we can make comparisons and see in what ways we are similar and in what ways we are different.”

The Hebrew

University scientists can now use their DNA methylation maps to reconstruct an

85% accurate portrait of early man, said Carmel. But the police are still out

of luck: Carmel said his methodology is not (yet) applicable to modern man.

3D RECONSTRUCTION OF DANISOVAN PAIR

|

| 3D MAX FILE OF DANISOVAN RECONSTRUCTION |

.jpg)

Online Movies

Online Movies

ReplyDeleteI love the movement in your work

ReplyDeleteThe emotion you capture is so real

ReplyDeleteYou always find beauty in the details

ReplyDeleteThe contrasts in this are so striking

ReplyDeleteYour process must be fascinating

ReplyDeleteI can feel the passion in this work