The Nobel Assembly at

Karolinska Institutet has today decided to award

the 2016 Nobel Prize

in Physiology or Medicine

to

Yoshinori Ohsumi

for his discoveries

of mechanisms for autophagy

Summary

This year's Nobel

Laureate discovered and elucidated mechanisms underlying autophagy, a

fundamental process for degrading and recycling cellular components.

The word autophagy

originates from the Greek words auto-, meaning "self", and phagein,

meaning "to eat". Thus,autophagy denotes "self eating".

This concept emerged during the 1960's, when researchers first observed that

the cell could destroy its own contents by enclosing it in membranes, forming

sack-like vesicles that were transported to a recycling compartment, called the

lysosome, for degradation. Difficulties in studying the phenomenon meant that

little was known until, in a series of brilliant experiments in the early

1990's, Yoshinori Ohsumi used baker's yeast to identify genes essential for autophagy.

He then went on to elucidate the underlying mechanisms for autophagy in yeast

and showed that similar sophisticated machinery is used in our cells.

Ohsumi's discoveries

led to a new paradigm in our understanding of how the cell recycles its content.

His discoveries opened the path to understanding the fundamental importance of

autophagy in many physiological processes, such as in the adaptation to

starvation or response to infection. Mutations in autophagy genes can cause

disease, and the autophagic process is involved in several conditions including

cancer and neurological disease.

Degradation – a

central function in all living cells

In the mid 1950's

scientists observed a new specialized cellular compartment, called an

organelle, containing enzymes that digest proteins, carbohydrates and lipids.

This specialized compartment is referred to as a "lysosome" and

functions as a workstation for degradation of cellular constituents. The

Belgian scientist Christian de Duve was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology

or Medicine in 1974 for the discovery of the lysosome. New observations during

the 1960's showed that large amounts of cellular content, and even whole

organelles, could sometimes be found inside lysosomes. The cell therefore

appeared to have a strategy for delivering large cargo to the lysosome. Further

biochemical and microscopic analysis revealed a new type of vesicle

transporting cellular cargo to the lysosome for degradation (Figure 1).

Christian de Duve, the scientist behind the discovery of the lysosome, coined

the term autophagy, "self-eating", to describe this process. The new

vesicles were named autophagosomes.

During the 1970's and

1980's researchers focused on elucidating another system used to degrade

proteins, namely the "proteasome". Within this research field Aaron

Ciechanover, Avram Hershko and Irwin Rose were awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in

Chemistry for "the discovery of ubiquitin-mediated protein

degradation". The proteasome efficiently degrades proteins one-by-one, but

this mechanism did not explain how the cell got rid of larger protein complexes

and worn-out organelles. Could the process of autophagy be the answer and, if

so, what were the mechanisms?

A groundbreaking

experiment

Yoshinori Ohsumi had

been active in various research areas, but upon starting his own lab in 1988,

he focused his efforts on protein degradation in the vacuole, an organelle that

corresponds to the lysosome in human cells. Yeast cells are relatively easy to

study and consequently they are often used as a model for human cells. They are

particularly useful for the identification of genes that are important in

complex cellular pathways. But Ohsumi faced a major challenge; yeast cells are

small and their inner structures are not easily distinguished under the

microscope and thus he was uncertain whether autophagy even existed in this

organism. Ohsumi reasoned that if he could disrupt the degradation process in

the vacuole while the process of autophagy was active, then autophagosomes

should accumulate within the vacuole and become visible under the microscope.

He therefore cultured mutated yeast lacking vacuolar degradation enzymes and

simultaneously stimulated autophagy by starving the cells. The results were

striking! Within hours, the vacuoles were filled with small vesicles that had

not been degraded (Figure 2). The vesicles were autophagosomes and Ohsumi's

experiment proved that authophagy exists in yeast cells. But even more

importantly, he now had a method to identify and characterize key genes involved

this process. This was a major break-through and Ohsumi published the results

in 1992.

Autophagy genes are

discovered

Ohsumi now took

advantage of his engineered yeast strains in which autophagosomes accumulated

during starvation. This accumulation should not occur if genes important for

autophagy were inactivated. Ohsumi exposed the yeast cells to a chemical that

randomly introduced mutations in many genes, and then he induced autophagy. His

strategy worked! Within a year of his discovery of autophagy in yeast, Ohsumi

had identified the first genes essential for autophagy. In his subsequent

series of elegant studies, the proteins encoded by these genes were

functionally characterized. The results showed that autophagy is controlled by

a cascade of proteins and protein complexes, each regulating a distinct stage

of autophagosome initiation and formation (Figure 3).

Autophagy – an

essential mechanism in our cells

After the

identification of the machinery for autophagy in yeast, a key question

remained. Was there a corresponding mechanism to control this process in other

organisms? Soon it became clear that virtually identical mechanisms operate in

our own cells. The research tools required to investigate the importance of

autophagy in humans were now available.

Thanks to Ohsumi and

others following in his footsteps, we now know that autophagy controls

important physiological functions where cellular components need to be degraded

and recycled. Autophagy can rapidly provide fuel for energy and building blocks

for renewal of cellular components, and is therefore essential for the cellular

response to starvation and other types of stress. After infection, autophagy can

eliminate invading intracellular bacteria and viruses. Autophagy contributes to

embryo development and cell differentiation. Cells also use autophagy to

eliminate damaged proteins and organelles, a quality control mechanism that is

critical for counteracting the negative consequences of aging.

Disrupted autophagy

has been linked to Parkinson's disease, type 2 diabetes and other disorders

that appear in the elderly. Mutations in autophagy genes can cause genetic

disease. Disturbances in the autophagic machinery have also been linked to

cancer. Intense research is now ongoing to develop drugs that can target

autophagy in various diseases.

Autophagy has been

known for over 50 years but its fundamental importance in physiology and

medicine was only recognized after Yoshinori Ohsumi's paradigm-shifting

research in the 1990's. For his discoveries, he is awarded this year's Nobel

Prize in physiology or medicine.

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2016

The Nobel Prize in Physics 2016 was divided, one half awarded to David J. Thouless, the other half jointly to F. Duncan M. Haldane and J. Michael Kosterlitz "for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter".

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics 2016 with one half to

David J. Thouless

University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

and the other half to

F. Duncan M. Haldane

Princeton University, NJ, USA

and

J. Michael Kosterlitz

Brown University, Providence, RI, USA

”for theoretical discoveries of topological phase transitions and topological phases of matter”

David J. Thouless, born 1934 in Bearsden, UK. Ph.D. 1958 from Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA. Emeritus Professor at the University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

F. Duncan M. Haldane, born 1951 in London, UK. Ph.D. 1978 from Cambridge University, UK. Eugene Higgins Professor of Physics at Princeton University, NJ, USA.

J. Michael Kosterlitz, born 1942 in Aberdeen, UK. Ph.D. 1969 from Oxford University, UK. Harrison E. Farnsworth Professor of Physics at Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

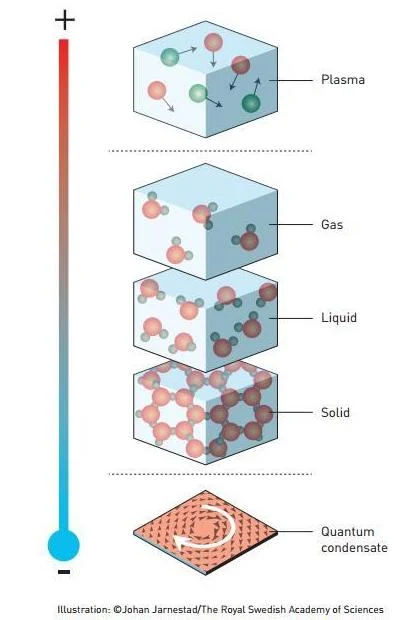

They revealed the secrets of exotic matter:

This year’s Laureates opened the door on an unknown world where matter can assume strange states. They have used advanced mathematical methods to study unusual phases, or states, of matter, such as superconductors, superfluids or thin magnetic films. Thanks to their pioneering work, the hunt is now on for new and exotic phases of matter. Many people are hopeful of future applications in both materials science and electronics.

The three Laureates’ use of topological concepts in physics was decisive for their discoveries. Topology is a branch of mathematics that describes properties that only change step-wise. Using topology as a tool, they were able to astound the experts. In the early 1970s, Michael Kosterlitz and David Thouless overturned the then current theory that superconductivity or suprafluidity could not occur in thin layers. They demonstrated that superconductivity could occur at low temperatures and also explained the mechanism, phase transition, that makes superconductivity disappear at higher temperatures.

In the 1980s, Thouless was able to explain a previous experiment with very thin electrically conducting layers in which conductance was precisely measured as integer steps. He showed that these integers were topological in their nature. At around the same time, Duncan Haldane discovered how topological concepts can be used to understand the properties of chains of small magnets found in some materials.

We now know of many topological phases, not only in thin layers and threads, but also in ordinary three-dimensional materials. Over the last decade, this area has boosted frontline research in condensed matter physics, not least because of the hope that topological materials could be used in new generations of electronics and superconductors, or in future quantum computers. Current research is revealing the secrets of matter in the exotic worlds discovered by this year’s Nobel Laureates.

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016 was awarded jointly to Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa "for the design and synthesis of molecular machines".

Jean-Pierre Sauvage, born 1944 in Paris, France. Ph.D. 1971 from the University of Strasbourg, France. Professor Emeritus at the University of Strasbourg and Director of Research Emeritus at the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), France.

Sir J. Fraser Stoddart, born 1942 in Edinburgh, UK. Ph.D. 1966 from Edinburgh University, UK. Board of Trustees Professor of Chemistry at Northwestern University, Evanston, IL, USA.

Bernard L. Feringa, born 1951 in Barger-Compascuum, the Netherlands. Ph.D.1978 from the University of Groningen, the Netherlands. Professor in Organic Chemistry at the University of Groningen, the Netherlands.

They developed the world's smallest machines:

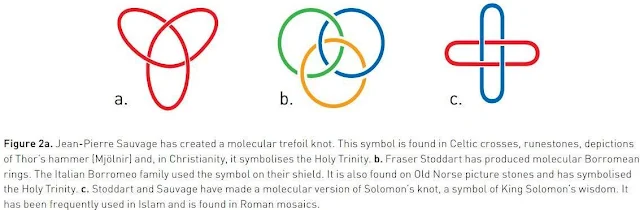

A tiny lift, artificial muscles and miniscule motors. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2016 is awarded to Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart and Bernard L. Feringa for their design and production of molecular machines. They have developed molecules with controllable movements, which can perform a task when energy is added.

The development of computing demonstrates how the miniaturisation of technology can lead to a revolution. The 2016 Nobel Laureates in Chemistry have miniaturised machines and taken chemistry to a new dimension.

The first step towards a molecular machine was taken by Jean-Pierre Sauvage in 1983, when he succeeded in linking two ring-shaped molecules together to form a chain, called a catenane. Normally, molecules are joined by strong covalent bonds in which the atoms share electrons, but in the chain they were instead linked by a freer mechanical bond. For a machine to be able to perform a task it must consist of parts that can move relative to each other. The two interlocked rings fulfilled exactly this requirement.

The second step was taken by Fraser Stoddart in 1991, when he developed a rotaxane. He threaded a molecular ring onto a thin molecular axle and demonstrated that the ring was able to move along the axle. Among his developments based on rotaxanes are a molecular lift, a molecular muscle and a molecule-based computer chip.

Bernard Feringa was the first person to develop a molecular motor; in 1999 he got a molecular rotor blade to spin continually in the same direction. Using molecular motors, he has rotated a glass cylinder that is 10,000 times bigger than the motor and also designed a nanocar.

2016's Nobel Laureates in Chemistry have taken molecular systems out of equilibrium's stalemate and into energy-filled states in which their movements can be controlled. In terms of development, the molecular motor is at the same stage as the electric motor was in the 1830s, when scientists displayed various spinning cranks and wheels, unaware that they would lead to electric trains, washing machines, fans and food processors. Molecular machines will most likely be used in the development of things such as new materials, sensors and energy storage systems.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2016 to

Oliver Hart

Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA

and

Bengt Holmström

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA

“for their contributions to contract theory”

The long and the short of contracts

Modern economies are held together by innumerable contracts. The new theoretical tools created by Hart and Holmström are valuable to the understanding of real-life contracts and institutions, as well as potential pitfalls in contract design.

Society’s many contractual relationships include those between shareholders and top executive management, an insurance company and car owners, or a public authority and its suppliers. As such relationships typically entail conflicts of interest, contracts must be properly designed to ensure that the parties take mutually beneficial decisions. This year’s laureates have developed contract theory, a comprehensive framework for analysing many diverse issues in contractual design, like performance-based pay for top executives, deductibles and co-pays in insurance, and the privatisation of public-sector activities.

In the late 1970s, Bengt Holmström demonstrated how a principal (e.g., a company’s shareholders) should design an optimal contract for an agent (the company’s CEO), whose action is partly unobserved by the principal. Holmström’s informativeness principle stated precisely how this contract should link the agent’s pay to performance-relevant information. Using the basic principal-agent model, he showed how the optimal contract carefully weighs risks against incentives. In later work, Holmström generalised these results to more realistic settings, namely: when employees are not only rewarded with pay, but also with potential promotion; when agents expend effort on many tasks, while principals observe only some dimensions of performance; and when individual members of a team can free-ride on the efforts of others.

In the mid-1980s, Oliver Hart made fundamental contri-butions to a new branch of contract theory that deals with the important case of incomplete contracts. Because it is impossible for a contract to specify every eventuality, this branch of the theory spells out optimal allocations of control rights: which party to the contract should be entitled to make decisions in which circumstances? Hart’s findings on incomplete contracts have shed new light on the ownership and control of businesses and have had a vast impact on several fields of economics, as well as political science and law. His research provides us with new theoretical tools for studying questions such as which kinds of companies should merge, the proper mix of debt and equity financing, and when institutions such as schools or prisons ought to be privately or publicly owned.

Through their initial contributions, Hart and Holmström launched contract theory as a fertile field of basic research. Over the last few decades, they have also explored many of its applications. Their analysis of optimal contractual arrangements lays an intellectual foundation for designing policies and institutions in many areas, from bankruptcy legislation to political constitutions.

Online Movies

Online Movies

No comments:

Post a Comment